Highlights

- Oil prices have traded in a range for the past few months, but headwinds are rising as we approach 2025.

- Many of the expected economic policies from the second Trump administration could weigh on oil prices over the next few years.

- Investor sentiment is flipping against the sector, as oil becomes less sensitive to geopolitical surprises.

In energy markets, 2022 feels like a lifetime away. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the price of oil shot up to $120 per barrel. US natural gas prices reached their highest level since 2008, while disruptions in European gas markets caused industrial stoppages and immense pain to households.

But as the initial invasion turned to a grinding war, oil prices normalized. Russia learned how to evade Western sanctions on its energy products. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) tried its best to keep prices high by eschewing increases in production. But oil production expansion in the US and other non-OPEC countries, combined with a recessionary backdrop in China, the world’s largest oil consumer, kept oil prices well below $90 for most of the last two years.

Oil teetering off the edge of its range

Oil prices

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

Oil now sits at the lower band of its recent range — and Donald Trump’s election could push it off the edge. Lower pump prices were one of Trump’s main campaign promises. Three Trump policies could weigh on oil prices: deregulation, general spending cuts and trade tariffs.

Trump and his new Secretary of Energy, fracking services executive Chris Wright, have pledged to “drill, baby, drill.” They can boost domestic oil production at the margin by working with Congress to streamline permitting, and they can cut down on environmental review timelines. But there’s a limit to what they can achieve. Producers won’t ramp up drilling just because the President says so. And US oil production is already at all time highs.

US oil production 3% above 2019 highs

US crude oil production by president’s party, million barrels per day

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

President-elect Trump’s planned “across-the-board” tariffs would likely put a damper on oil prices. Energy products would probably be excluded from tariffs, for political reasons. Gas prices are politically salient, and oil production is inelastic: it would take some time for US producers to ramp up operations to compensate for tariff-impacted oil imports.

Tariffs on non-oil products — which could potentially cover more than half of all US imports — would weigh on global growth. Morgan Stanley economists estimate a 1.4 percentage point hit to US GDP growth from US tariffs. Lower growth, both in the US and globally, could cause global oil demand to stay flat at its current levels in 2025, after expanding by just under 1% in 2024. Weak Chinese economic growth has been a key source of demand weakness in global oil markets, and we don’t expect Chinese GDP growth to pick up anytime soon, especially with a ramp up of tariffs on Chinese exports.

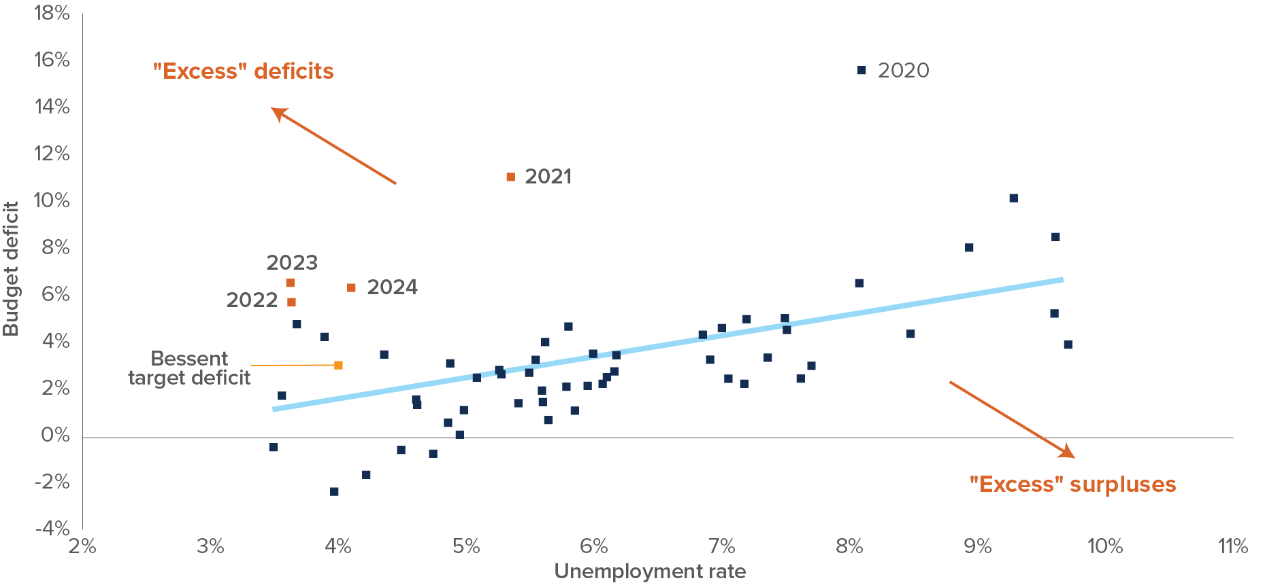

In the run-up to the presidential election, analysts saw ballooning budget deficits as a primary characteristic of a second Trump presidency. Such a fiscal expansion would boost growth — and inflation — in the short term. But the nomination of fiscally conservative hedge fund manager Scott Bessent as Secretary of the Treasury and the apparent outsized role Elon Musk has played in Trump’s first weeks as president-elect suggest forecasts of soaring deficits might have been premature.

Bessent has bandied about a deficit target of 3% of GDP, half the size of the current federal deficit, and a far cry from some economists’ double-digit Trump deficit forecasts. Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency has been tasked with finding $2 trillion in government spending (around 7% of GDP) to cut. Even if Bessent and Musk’s fiscal tightening efforts fizzle out, the deficit is unlikely to massively expand from current levels. Restrained deficits, combined with a tariff shock, are bad news for US oil demand.

Slashing the federal deficit to 3% would be a massive negative fiscal shock

US federal deficit (% of GDP) and US unemployment rate

Source: Bloomberg. Final data up to 2023. 2024 shows the Consensus Economics average forecast for 2024 unemployment rate and federal deficit. “Bessent target deficit” shows Scott Bessent’s 3% of GDP deficit target, along with the midpoint of the Federal Reserve’s estimate of long-run unemployment rate.

Source: Bloomberg. Final data up to 2023. 2024 shows the Consensus Economics average forecast for 2024 unemployment rate and federal deficit. “Bessent target deficit” shows Scott Bessent’s 3% of GDP deficit target, along with the midpoint of the Federal Reserve’s estimate of long-run unemployment rate.

On the supply side of oil markets, Trump’s election is more of a mixed bag. As mentioned above, US oil production could expand at the margin from regulatory loosening. On the other hand, Trump could tighten the geopolitical screws on Iran and Venezuela, which have been successfully skirting US sanctions to sell their oil on world markets. Pressure on Iran — the seventh largest global producer of crude, with close to 5% of global supply — could seriously disrupt oil markets.

In recent years, the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) has played a non-negligeable role in oil markets. When Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent oil prices soaring in 2022, the government tapped the SPR to smooth the shock. The Biden administration started refilling the SPR towards the end of last year, but it remains 300 million barrels below its 2019 levels. Trump’s team has hinted that he would call on Congress to appropriate funds to replenish the SPR. He doesn’t really have a choice: the salt caverns in which the SPR is stored will degrade if left empty for a long period. But we also believe that Trump would be quick to draw on the SPR if a new oil shock emerges.

With Trump’s election, plans to refill the SPR are in limbo

Crude oil inventories, million barrels

Source: Bloomberg. Seasonal adjustment to commercial inventories by the author.

Source: Bloomberg. Seasonal adjustment to commercial inventories by the author.

We now have a negative view of the US energy sector, and we are far from the only ones. The short interest on the main US Energy sector ETF shot up ahead of the election. Short sellers — who tend to be sophisticated investors — likely dislike the combination of declining sector profitability and risks to commodity prices. Plus, oil prices have been less sensitive to geopolitical surprises over past months, reducing oil’s risk-hedging potential.

Short interest on the US energy sector jumped ahead of the election

Days to cover on SPDR sector ETFs

Source: Bloomberg. Days to cover measures of how many days it would take for all outstanding shorted shares to be closed out at current market volumes.

Source: Bloomberg. Days to cover measures of how many days it would take for all outstanding shorted shares to be closed out at current market volumes.

Risks to the energy sector are more salient for the Canadian stock market than most other global stock markets. Energy stocks make up around 18% of the TSX Composite index, vs. 4% for the S&P 500. While our negative view on the energy sector is directly expressed through a bet against the US energy sector, we also have a negative view on the Canadian stock market. The Canadian market is generally overvalued, is subject to tariff risks and could be dragged down by a sluggish economy. Its oil exposure is the cherry on top.

Multi-Asset Strategies Team’s investment views

Tactical summary

Source: Mackenzie Investments

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Source: Mackenzie Investments

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Positioning highlights

Turning neutral on duration: We’ve mostly shied away from duration over the past few years. We preferred leaning into stocks for returns and saw US recession odds as overblown. We still don’t expect a recession anytime soon, given the US government’s continuing deficits and the Federal Reserve’s eagerness to cut rates ahead of a contraction. But we also don’t see high risks of an inflation surge over the next few quarters, the ultimate risk for fixed income. Trade tariffs would cause prices to jump in the US but are not an inflationary shock. Once the one-time effect on prices has passed, future inflation could be lower than without the tariffs, given trade wars could depress economic growth. Accordingly, we’re comfortable taking a roughly neutral position.

Still not ready to bet against equities: While global stock markets are clearly expensive, valuations are not at extremes, as they were, for example, at the end of 2021. Investor positioning is supportive in the medium term, and we expect the US to avoid a recession as a slew of rate cuts help stabilize the economy. This leaves us with a broadly neutral view on global equities.

Turning bearish on the euro: Last month, we closed our overweight in the euro against the Canadian dollar. Financial market inflows have been turning into outflows in recent months, a bad omen for the euro. Plus, revised estimates of long-term euro fair value, using recently released macro data, suggests that the euro is less cheap than previously thought.

Upside potential in small caps: Small cap stocks are not a bargain, but they are somewhat cheaper than large cap stocks across sectors, as last month’s commentary outlined. Small caps’ window of outperformance is narrow: it requires both Fed rate cuts and a resilient US economy. But if the post-COVID economic overheating does resolve with a soft landing, the valuation gap between small and large cap could close quickly.

Canadian landing: The macro situation in Canada is much more dire than in the US. The Canadian economy has an argument for the most disappointing advanced economy year-to-date. The job market is deteriorating quickly, especially when adjusting for working population growth and government hiring. We like Canadian government bonds, but dislike Canadian stocks and the Canadian dollar, especially against currencies other than the US dollar. Looming US tariffs on Canadian exports are an additional risk, with President Trump recently singling out Canada as a tariff target.

Commodity-exporting emerging market (EM) currencies: Commodity-exporting EMs are well situated to outperform in this macro environment. Their budgetary and external balances have improved amid high global nominal growth and high commodity prices. Their central banks started raising rates much earlier than the rest of the world. As a result, they have generally reached the end of their tightening cycle, reducing the risk of overtightening into a recession. But the level of rates remains high, offering positive carry over most other currencies. On the other hand, we hold a negative view on the currencies of Asian EM countries. Their external positions have severely deteriorated, and their interest rates are relatively low. Thailand’s prospects have improved significantly, but South Korea and the Philippines are still stuck in the macro mud.

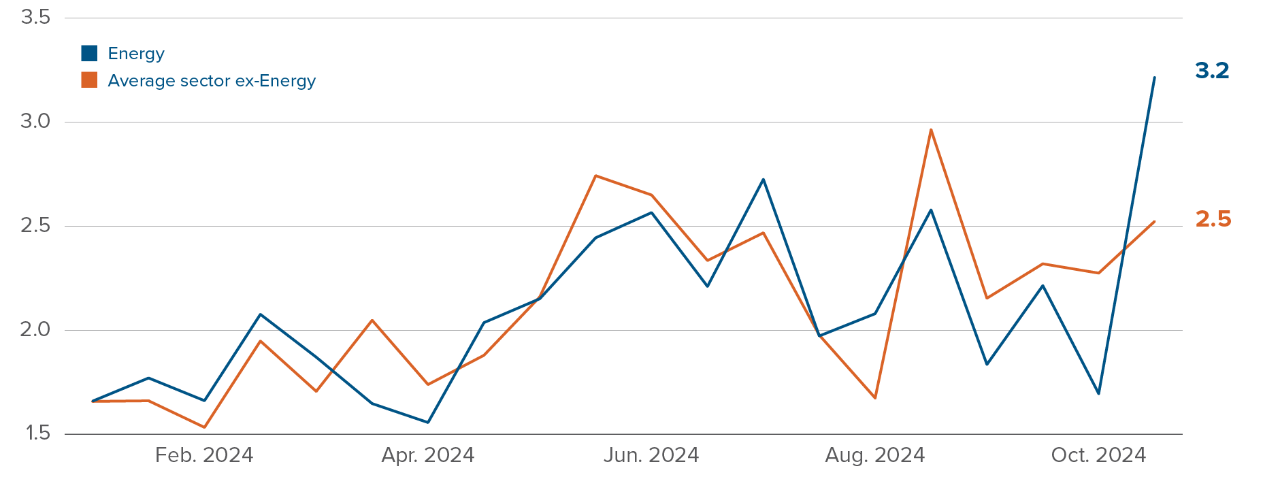

Doubling down on European duration: Inflation rates have been pulling back in a synchronized manner across euro area countries. In recent weeks, even solid-but-unimpressive economic indicator prints have been met with rallies in long-term rates, as markets price out the right tail scenario of an inflation spiral. At the other end of the spectrum, United Kingdom and Australian duration are less attractive.